ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to your office for a routine physical. He has a 30 pack-year smoking history. When you talk to him about smoking cessation, he tells you he’s tried to stop more than once, but he can’t seem to stay motivated. You find no evidence of chronic lung disease and do not perform spirometry screening. (The US Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend spirometry for asymptomatic patients.) But could spirometry have therapeutic value in this case?

Smoking is the leading modifiable risk factor for mortality in the United States,2 and smoking cessation is the most effective intervention. Nortriptyline, bupropion, nicotine replacement agents, and varenicline are effective pharmacological treatments.3 Adding counseling to medication significantly improves quit rates (estimated odds ratio [OR]=1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2-1.6).3 Nonetheless, physicians’ efforts to help patients stop smoking frequently fail.

But another option has caught—and held—the attention of researchers.

The promise of biomarkers

It has long been suspected that presenting smokers with evidence of tobacco’s harmful effect on their bodies—biomarkers—might encourage them to stop. Biomarkers that have been tested in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) include spirometry, exhaled carbon monoxide measurement, ultrasonography of carotid and femoral arteries, and genetic susceptibility to lung cancer, as well as combinations of these markers. But the results of most biomarker studies have been disappointing. A 2005 Cochrane Database review found insufficient evidence of the effectiveness of these markers in boosting quit rates.4

Lung age, a biomarker that’s easily understood

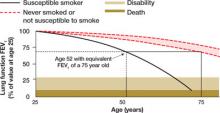

Lung age, a clever presentation of spirometry results, had not been tested in an RCT prior to the study we summarize below. Defined in 1985, lung age refers to the average age of a nonsmoker with a forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) equal to that of the person being tested ( FIGURE 1 ). The primary purpose was to make spirometry results easier for patients to understand, but researchers also envisioned it as a way to demonstrate the premature lung damage suffered as a consequence of smoking.5

FIGURE 1

Translating FEV1 into lung age1

STUDY SUMMARY: Graphic display more effective than FEV1 results

This study was a well-done, multicenter RCT evaluating the effect on tobacco quit rates of informing adult smokers of their lung age.1 Smokers ages 35 and older from 5 general practices in England were invited to participate. The authors excluded patients using oxygen and those with a history of tuberculosis, lung cancer, asbestosis, bronchiectasis, silicosis, or pneumonectomy. The study included 561 participants with an average of 33 pack-years of smoking, who underwent spirometry before being divided into an intervention or a control group. The researchers used standardized instruments to confirm the baseline comparability of the 2 groups.

Subjects in both groups were given information about local smoking cessation clinics and strongly encouraged to quit. All were told that their lung function would be retested in 12 months.

The controls received letters with their spirometry results presented as FEV1. In contrast, participants in the intervention group received the results in the form of a computer-generated graphic display of lung age ( FIGURE 2 ), which was further explained by a health care worker. They also received a letter within 1 month containing the same data. Participants were evaluated for smoking cessation at 12 months, and those who reported quitting received confirmatory carbon monoxide breath testing and salivary cotinine testing. Eleven percent of the subjects were lost to follow-up.

FIGURE 2

Lung age helps spirometry pack a bigger punch

Drawing a vertical line from the patient’s age (on the horizontal axis) to reach the solid curve representing the lung function of the “susceptible smoker” and extending the line horizontally to reach the curve with the broken lines representing “never smokers” graphically shows the patient’s lung age and the accelerated decline in lung function associated with smoking. The patient shown here is a 52-year-old smoker with FEV1 equivalent to a 75-year-old nonsmoker.

Source: Parkes G et al. BMJ. 2008;336:598-600. Reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group.