CASE: A 26-year-old woman came to our emergency department with shortness of breath—a symptom that had begun 2 weeks earlier and was getting steadily worse. She had a history of severe, persistent asthma, and had been admitted to the ICU—but not intubated—9 months earlier. Now, she reported dyspnea with even mild exertion, which inhalers failed to relieve.

The patient also had a cough and had recently begun producing thick, green sputum, but said she’d had no chest pain, fever, or lower extremity swelling. The young woman lived with her parents, both of whom smoked heavily, but denied tobacco or alcohol use herself. She had not taken antibiotics in the past 6 months.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile, mildly tachypneic, and had a heart rate of 125 bpm. She was saturating 80% on ambient air and 95% on 2 liters per minute via nasal cannula; her lung exam was significant for diffuse wheezes and rhonchi, but the remainder of the physical exam was normal.

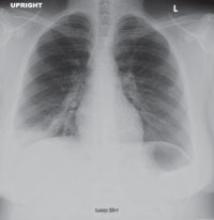

Lab tests revealed a white blood cell count of 25,200/mcL, with 81% neutrophils. Blood and urine cultures were preliminarily negative. We sent a sputum sample to be cultured and took chest x-rays. Posterior-anterior (PA) (FIGURE 1) and lateral (FIGURE 2) radiographs showed a dense right lower lobe inflltrate.

We diagnosed community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), coupled with an acute exacerbation of asthma, and admitted the patient to the hospital. We started her on intravenous (IV) moxifloxacin, parenteral steroids, and nebulized albuterol and ipratropium. But by the patient’s third day in the hospital, her white blood cell count had climbed to 34,500/mcL, and she still required oxygen by nasal cannula.

FIGURE 1 PA x-ray shows right lower lobe infiltrate

FIGURE 2 Dense infiltrate on lateral view

WHY DIDN’T THIS PATIENT RESPOND TO DRUG THERAPY?

CAP complicated by CA-MRSA

Initially, this appeared to be a rather straightforward case of CAP and asthma. The return of the sputum cultures on day 4, showing positive results for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), indicated that this was not the case. Sensitivity analysis revealed intermediate susceptibility to moxifloxacin and sensitivity to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), vancomycin, and linezolid.

We switched the patient’s antibiotic from moxifloxacin to parenteral linezolid. She responded rapidly. On day 5, the patient was successfully weaned from O2 and converted to oral linezolid; the following day, she was discharged, with orders to complete an 8-day course of linezolid and an appointment with her family physician for the following week. At follow-up, she was doing well.

Cultures are crucial if results would alter Tx

In 2007, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) published guidelines on the management of CAP1—a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of select features, including cough, fever, sputum production, and pleuritic chest pain. (Imaging of the chest may be used to support the diagnosis, but is not required.)

Following a site-of-care decision, ideally made with the help of a severity-of-illness scoring system such as the CURB-65 (Confusion, Urea nitrogen, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, 65 years of age and older) or Pneumonia Severity Index, the guidelines recommend cultures whenever the result is likely to significantly alter standard empiric treatment.1

Pretreatment blood samples for culture should be obtained (strength of recommendation: A, well-conducted randomized controlled trials). The IDSA/ATS CAP guidelines also recommend an expectorated sputum sample for stain and culture for patients admitted to the ICU, as well as for those with a presentation suggestive of CAP who:

- have failed outpatient treatment;

- abuse alcohol;

- have severe structural or obstructive lung disease;

- or have pleural effusion.1

In our patient’s case, we obtained a sputum culture on admission because of her severe asthma. She was persistently hypoxic during her initial days in the hospital, and when the sputum culture returned positive for MRSA, her regimen of antibiotics was adjusted.

Suspect CA-MRSA when CAP is severe

Although MRSA has traditionally been thought of as a nosocomial pathogen, infections caused by distinct CA-MRSA strains are on the rise. An estimated 1% to 10% of CAP cases are caused by S aureus, but the percentage of those strains that are resistant to methicillin is not known.2

Clinical risk factors for S aureus CAP include end-stage renal disease, injection drug use, prior influenza, and prior antibiotic therapy, especially with fluoroquinolones.1 How-ever, CA-MRSA CAP often affects children and healthy young adults without any risk factors.3,4

Additionally, CAP that is caused by CA-MRSA is typically severe, often involving empyema, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cavitary pneumonia, or severe sepsis.5 Consider a diagnosis of CA-MRSA CAP in patients who present with cavitary infiltrates without risk factors for anaerobic aspiration, such as syncope, seizures, alcohol abuse, or esophageal motility disorders.1