› Seek immediate emergency care for patients with chest pain that is exertional, radiating to one or both arms, similar to or worse than prior cardiac chest pain, or associated with nausea, vomiting, or diaphoresis. A

› Be aware that patients with chest pain that is stabbing, pleuritic, positional, or reproducible with palpation are at very low risk for acute coronary syndrome and most likely have chest wall pain. A

› Consider a 2-week course of high-dose proton-pump inhibitor therapy to help identify patients whose chest pain may be from undiagnosed gastroesophageal reflux disease. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Your patient, Amy Z, age 58, was given a diagnosis of hypertension 10 years ago and since then has been maintained on hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg/d and lisinopril 10 mg/d. In the office today, she reports intermittent chest tightness and heaviness. She has no history of coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease. She attributes her chest discomfort to emotional stress. She recently started a job after having been unemployed, but still has no health insurance and is concerned about losing her house.

She denies orthopnea and resting or exertional dyspnea, and says she never gets chest pain while climbing stairs. Her blood pressure is elevated at 180/110 mm Hg, but her other vital signs are normal (pulse, 70 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute). On physical examination, she has no venous distension in her neck and her lungs are clear. A cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm, with a normally split S1 and S2 and no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Palpation of the chest does not reproduce her chest pain.

You are concerned that your patient’s chest pain could be from heart disease, but she wants to defer additional testing because of the cost, stating, “It’s all due to my stress.”

How would you proceed?

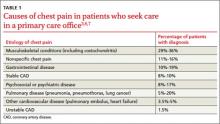

Musculoskeletal chest wall pain is the most common cause of chest pain in patients who seek treatment in the office, followed by GI disease and stable heart disease.

Whether they go to the emergency department (ED) or to their family physician’s office, most patients who seek treatment for chest pain don’t have life-threatening cardiac illness. Of the 8 million patients who visit an ED for chest pain each year, only 13% are diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).1,2 Among those seen for chest pain in a primary care office, only a minority (approximately 1.5%) have unstable heart disease.3-5 Cross-sectional studies indicate that musculoskeletal chest wall pain (or “chest wall syndrome [CWS]”) is the most common cause of chest pain in patients who seek treatment in the office, followed by gastrointestinal (GI) disease, stable heart disease, psychosocial or psychiatric conditions, pulmonary disease, and other cardiovascular conditions (TABLE 1).3,6,7

When evaluating patients with chest pain in the office, the challenge is to appropriately evaluate and manage those who are at low risk of ACS, while at the same time identifying and arranging prompt transfer or referral for the minority of patients who are at high cardiac risk. This article describes how to determine which patients require emergency treatment, which tools to use to screen for ACS and other potential causes of chest pain, and how to proceed when initial evaluation and testing do not point to a clear diagnosis.

Start with the ABCs

When a patient presents in primary care with a chief complaint of chest pain, it’s of course critical that you quickly determine if he or she is stable by evaluating the “ABCs” (airway, breathing, and circulation). Any potentially unstable patient should be immediately transferred for emergency care.8 A patient who shows no signs of respiratory distress and whose vital signs are within a normal range is unlikely to be acutely unstable, and can be further evaluated in the office.

If the patient is stable, obtain a history of the onset and evolution of the chest pain, especially its location, quality, duration, and aggravating or alleviating factors. Also ask about a personal or family history of heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia, and about tobacco use. While the presence of any of these cardiac risk factors may increase suspicion for a cardiac cause for chest pain, the absence of such factors does not eliminate the need for a careful diagnostic evaluation.

Patients with “typical” chest pain have a higher risk of ACS. In a 2005 review of observational prospective and retrospective studies and systematic reviews, Swap et al9 corroborated the description of “typical” anginal chest pain, indicating that patients whose chest pain is exertional, radiating to one or both arms, similar to or worse than prior cardiac chest pain, or associated with nausea, vomiting, or diaphoresis are at high risk for ACS (TABLE 2).9 These researchers also found that chest pain that is stabbing, pleuritic, positional, or reproducible with palpation suggests that a patient is at low risk for ACS. Pain that is not exertional or that is in a small inframammary area of the chest also suggests a low risk for ACS.9