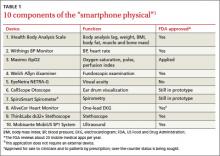

In April, hundreds of attendees at TEDMED, a conference on medical innovation, waited in line for a “smartphone physical.” Curated by Shiv Gaglani, a medical student and an editor at the medical technology journal Medgadget, the exam involved 10 apps that turn an ordinary smartphone into a medical device (TABLE 1).1 Among them were the AliveCor Heart Monitor (pictured at right), which produces a one-lead EKG in seconds when a patient’s fingers or chest are pressed against the electrodes embedded in the back of what is essentially a phone case2; a pulse oximeter, and an ultrasound that can capture images of the carotid arteries.1

All but one of the apps is paired with a physical component, such as an ultrasound wand or otoscope. The exception is SpiroSmart, an app that uses the phone’s The AliveCor app and Heart Monitor—a smartphone case fitted with sensors—can generate a one-lead EKG tracing in seconds.built-in microphone and lip reverberations to assess lung function. Shwetak Patel, PhD, of the University of Washington, one of its developers, told JFP that the accuracy of SpiroSmart has been found to be within 5% of traditional spirometry results.3

While smartphone physicals are not likely to be integrated into family practice for some time to come, Glen Stream, MD, board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians, predicts that integration of some of their features is not too far away. “The spirometry application is an especially good one; it addresses one of the top 5 chronic conditions that contribute to health care costs,” Dr. Stream said. The apps will be beneficial, he added, as long as they “are used in a way that contributes, to, rather than detracts from, collaboration between patients and physicians.”

For now, Dr. Stream and many of his fellow FPs use mobile devices and medical apps primarily to access reference materials, both in and out of the exam room. Some have begun “prescribing” apps to tech-savvy patients. Still others have never used a medical app, either because they prefer a desktop or laptop computer to a smartphone or tablet or because, as one FP put it, "I have a dumb phone."

Wherever you fall on the spectrum, it’s a safe bet that you’re going to be increasingly inundated by the many manifestations of mobile health (mHealth).

Epocrates is No. 1 reference app

The number of medical/health apps for smart-phones or tablets is difficult to pin down; estimates range from 17,000 to more than 40,000, and growing.4 More is known about physician use of smartphones and tablets.

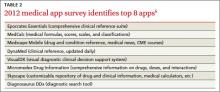

A March 2013 survey of nearly 3000 physicians found that 74% use smartphones at work and 43% use them to look up drug information.5 The favorite tool? A 2012 survey conducted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine to identify the best medical apps put Epocrates at the top of the list (TABLE 2).6 Epocrates was the very first app cited by virtually all the FPs interviewed for this article, as well.

Other drug references cited tend to be patient-specific. Colan Kennelly, MD, a clinical educator at the Good Samaritan Family Medicine Residency in Phoenix, finds LactMed particularly useful. Developed by the National Library of Medicine and part of its Toxicology Data Network, the app lets you pull up medications quickly and see whether and how they will affect breastfeeding.

Another favorite of Kennelly’s is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s ePSS (electronic Preventive Services Selector) app designed to help primary care clinicians identify the preventive services that are appropriate for their patients. “You just plug in a patient’s age and sex”—(pregnancy, tobacco use, and whether the patient is sexually active are also considered)—“and it tells you what you should be checking for,” Dr. Kennelly said.

The benefits of mobile textbooks

Textbook apps and online texts are slowly gaining in popularity. A recent survey by Manhattan Research found that in 2013 for the first time, usage of electronic medical texts surpassed that of print editions.7 Part of the appeal is that mobile texts are easy to tote. “Apps make it possible to carry around information from a number of textbooks with no added weight,” said Richard Usatine, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and editor of JFP’s Photo Rounds column. Dr. Usatine is also a principal of Usatine Media, which turns medical reference materials into apps.

Dr. Usatine’s own experience is a case in point. He recently used a textbook app to prepare to take his boards (for the fifth time). “I’ve brushed up each time,” he said, “but this time I really studied because it was fun.