› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

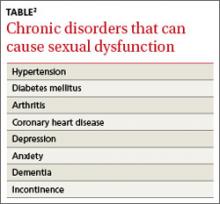

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1