› Tell patients who are potential candidates for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that it has been demonstrated to be effective in treating anxiety and trauma-related disorders. A

› Motivate patients by pointing out that CBT is short-term therapy that is cost-effective and has the potential to be more beneficial than medication. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Darla S, a 42-year-old being treated for gastrointestinal (GI) distress, has undergone multiple tests over the course of the year, including a colonoscopy, an endoscopy, and a food allergy work-up. All had negative results. Medication trials—with proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, and prokinetics, among others—have not brought her any relief. The patient recently began taking sertraline 200 mg/d, which seemed to be helping. But on her latest visit, Ms. S requests a prescription for a sleeping pill. When asked what’s been keeping her up, the patient confides that she recently began having nightmares relating to a sexual assault that occurred several years ago.

If Ms. S were your patient, what would you recommend?

Family physicians (FPs) often encounter patients who are experiencing psychological distress, particularly anxiety.1 This may become evident when you’re treating one problem, such as low back pain or GI distress, but come to realize that anxiety is a key contributing factor or cause. Or you may discover that an anxiety or trauma-related disorder is complicating or interfering with treatment—preventing a patient with heart disease from quitting smoking, exercising regularly, or following a heart-healthy diet, for example.

Psychotropic medication is an option in such cases, of course. But the drugs often have adverse effects or interact with other medications the patient is taking, and their effects typically last only as long as the course of treatment. Being familiar with effective nonpharmacologic treatments—most notably, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—will help you provide such patients with optimal care.

Advantages. CBT has several advantages that supportive counseling, traditional psychotherapy, and other nonpharmacologic treatments for psychological disorders do not: It is time-limited, typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks; skill-based; and goal-oriented. It also has a large amount of data to support it.2-4

Chances are you are familiar with the basic elements of CBT—challenging problematic beliefs, ensuring an increase in pleasant activities, and providing extended exposure to places or activities that trigger avoidance and/or arousal so that these responses are gradually diminished.2 However, there is not one single model of CBT. Rather, there are specific protocols for the conditions included in this review (TABLE 1).5

But before we get to the protocols, let’s first look at the evidence.

Meta-analyses demonstrate efficacy and effectiveness

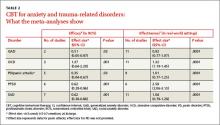

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have consistently found CBT to reduce symptoms associated with anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Foremost among them are a metaanalysis by Hofmann and Smits6 of randomized placebo-controlled studies that assessed CBT’s efficacy and a meta-analysis by Stewart and Chambless7 that focused instead on effectiveness studies—ie, those assessing CBT in less-controlled, real-world practice. The findings are highlighted in TABLE 2.6,7

A 2012 review of meta-analyses of CBT8 for a broader range of psychological disorders found it to be more effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD) than control conditions, such as placebo, and often more effective than other treatments. Notably, CBT was shown to be more effective than relaxation therapy for PD, more effective in the long term than psychopharmacology for SAD, and more effective than supportive counseling for PTSD.

Cognitive processing and exposure therapy for PTSD

Two types of CBT have been found to be particularly effective in treating PTSD: cognitive processing therapy and exposure therapy. Each has specific protocols, although treatment often has some components of each.9

Cognitive processing therapy, a firstline treatment for PTSD, was initially developed for the treatment of rape victims,10 but has been found to be effective in treating combat-related PTSD, as well.11 It incorporates the core elements of cognitive therapy—identifying false or unhelpful trauma-related thoughts, then evaluating the evidence for and against them so the patient learns to consider whether these problematic thoughts are the result of cognitive bias or error and develop more realistic and/or useful thoughts. Cognitive processing therapy, however, focuses primarily on issues of safety, danger, and trust relating to patients’ views of themselves, others, and the world. Patients are asked to write, and then read, a narrative of the trauma they endured to help them challenge troubling thoughts about it.10